Note: this is the text of a blog post that originally appears on the Cheshire Library blog.

I used to enjoy cooking and baking once, but life happened (as it does), and over the years it evolved from a fun hobby into a chore. I’ve bounced back from my low point of lockdown-era frozen buffalo chicken strips, but cooking is still not something that brings me joy. Even when I try new recipes. No, especially when I try new recipes. There’s too much thinking, too many variables, not enough autopilot. I groan whenever my produce subscription boxes send me yet another unidentifiable root vegetable that requires a consultation with the internet. And if a new recipe starts going sideways – I’m looking at you, butternut squash gnocchi that I made for Christmas – I tend to season the cooking process with a heaping spoonful of expletives.

Luckily, my attempts at culinary novelty usually turn out pretty good. But I still prefer to fall back on my tried-and-true recipes: the ones I could do in my sleep, without sounding like I’m performing a read-aloud from the recipe section of Bad Manners. I applaud the home cooks who enjoy tackling new kitchen adventures. And I especially applaud those who can do it with little ones running around. If you need to clear some table space for creativity, or if you’re just trying to cook off this week’s mystery veg without introducing young ears to – ahem – new vocabulary, why not keep your kids safely occupied with a book? These fun and engaging stories cover some of our favorite foods, from nachos to chocolate chip cookies. They might even inspire your kids to go beyond the role of Brownie Batter Bowl Licker and move up to Chef-in-Training… even if the position is only open on low-stress dinner nights where the only duty is arranging the frozen buffalo chicken strips (or more likely, dinosaur chicken nuggets) on a baking sheet.

Magic Ramen: The Story of Momofuku Ando. Every day, Ando Momofuku would retire to his lab–a little shed in his backyard. For years, he’d dreamed about making a new kind of ramen noodle soup that was quick, convenient, and tasty to feed the hungry people he’d seen in line for a bowl on the black market following World War II. “Peace follows from a full stomach,” he believed. With persistence, creativity, and a little inspiration, Ando prevailed. This is the true story behind one of the world’s most popular foods.

How the Cookie Crumbled: The True (and Not-So-True) Stories of the Invention of the Chocolate Chip Cookie.Everyone loves chocolate chip cookies! But not everyone knows where they came from. Meet Ruth Wakefield, the talented chef and entrepreneur who started a restaurant, wrote a cookbook, and invented this delicious dessert. But just how did she do it, you ask? That’s where things get messy!

Chef Roy Choi and the Street Food Remix. For Chef Roy Choi, food means love. It also means culture, not only of Korea where he was born, but the many cultures that make up the streets of Los Angeles, where he was raised. So remixing food from the streets, just like good music—and serving it up from a truck—is true to L.A. food culture. People smiled and talked as they waited in line. Won’t you join him as he makes good food smiles?

Dumpling Dreams: How Joyce Chen Brought the Dumpling from Beijing to Cambridge.

A rhyming introduction to the life and influence of famous chef Joyce Chen describes how she immigrated to America from communist China and how she helped popularize Chinese food in the northeastern United States.

The Hole Story of the Doughnut. In 1843, 14-year old Hanson Gregory left his family home in Rockport, Maine and set sail as a cabin boy on the schooner Achorn, looking for high stakes adventure on the high seas. Little did he know that a boat load of hungry sailors, coupled with his knack for creative problem-solving, would yield one of the world’s most prized pastries.

Minette’s Feast: The Delicious Story of Julia Child and Her Cat. While Julia is in the kitchen learning to master delicious French dishes, the only feast Minette is truly interested in is that of fresh mouse!

Nacho’s Nachos: The Story Behind the World’s Favorite Snack. Celebrating 80 Years of Nachos, this book introduces young readers to Ignacio “Nacho” Anaya and tells the true story of how he invented the world’s most beloved snack in a moment of culinary inspiration.

And because my editor would be very unhappy if I got this far without mentioning at least one cookbook, here’s our newest titles to help your Chef-in-Training build their skills:

The Big, Fun Kids Cookbook. Each recipe is totally foolproof and easy to follow, with color photos and tips to help beginners get excited about cooking. The book includes recipes for breakfast, lunch, dinner, snacks and dessert — all from the trusted chefs in Food Network’s test kitchen.

Kitchen Explorers! 60+ Recipes, Experiments, and Games for Young Chefs. What makes fizzy drinks fizzy? Can you create beautiful art using salt? Or prove the power of smell with jelly beans? Kitchen Explorers brings the kitchen alive with kid-tested and kid-approved recipes, fun science experiments, hands-on activities, plus puzzles, word games, and more.

Grandma and Me in the Kitchen. This cookbook, made just for Grandma and her little chefs, is full of foods they will both love to cook together! Along with recipes for breakfast, lunch, dinner, snacks, and desserts are tips for creating traditions and finding ways to celebrate the everyday wonderfulness of just being together.

We have tons more cookbooks in the children’s and adults sections of the library. What are you planning to cook up in 2021?

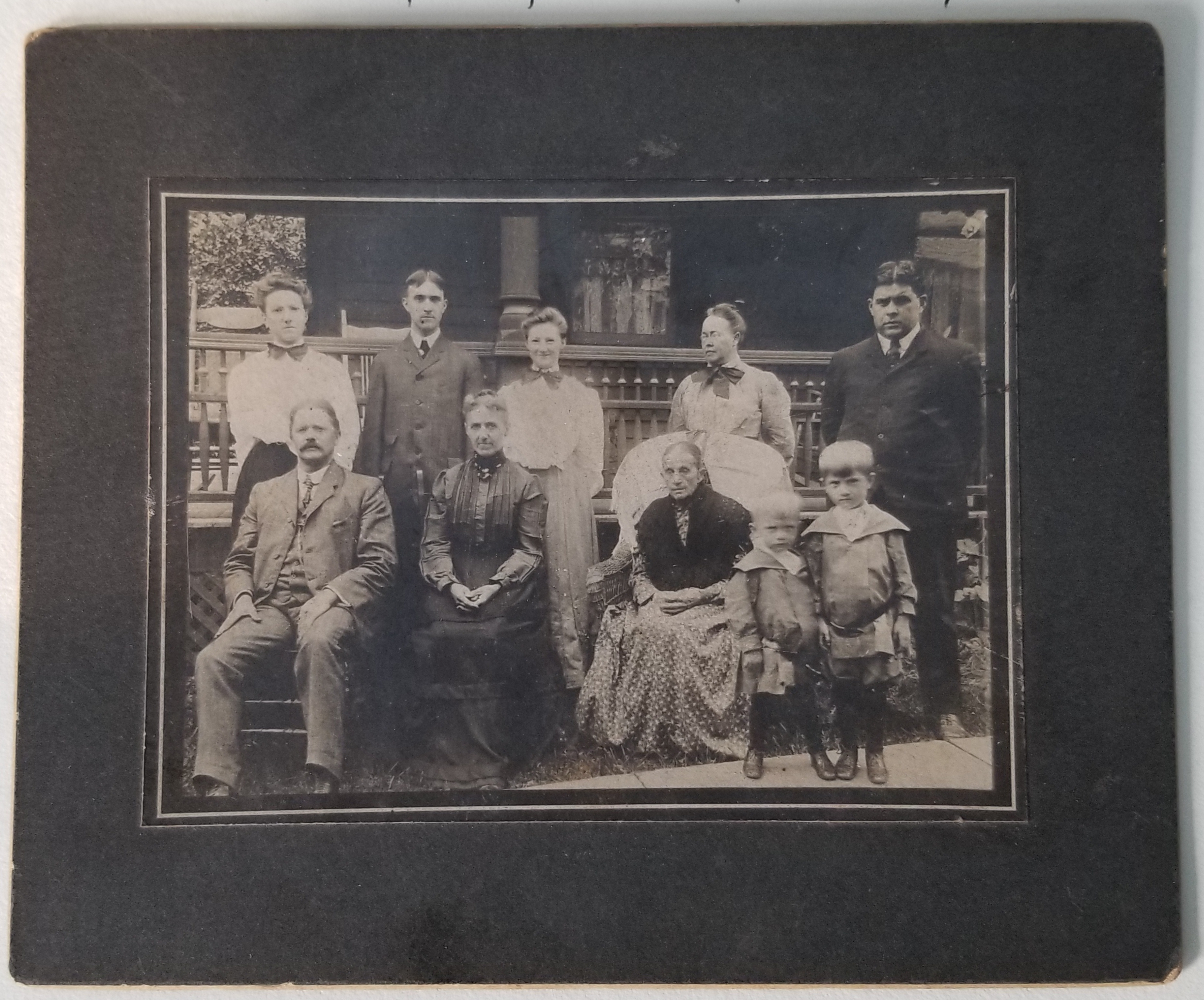

When my grandmother cleaned out her house, I inherited a collection of old photos, documents, and books. Many items were of unknown origins, collected by a long-dead relative and placed in a series of boxes and bags, which in turn was tucked into a closet until it emerged one Sunday afternoon. I was fascinated. I spent hours going through the pages of the books and turning over the photos to see the names. I grew to recognize them, even if I couldn’t exactly connect them to me. Here in this local history book is a Balliet: the name I carried for most of my life. This photo, a Bloss. Here’s a Schneider, a Kern. But nothing haunted me quite like the handwritten inscription that prefaced a photo album: “Presented to Kate E. Haines by her Affectionate Mother, July 18, 1866.”

When my grandmother cleaned out her house, I inherited a collection of old photos, documents, and books. Many items were of unknown origins, collected by a long-dead relative and placed in a series of boxes and bags, which in turn was tucked into a closet until it emerged one Sunday afternoon. I was fascinated. I spent hours going through the pages of the books and turning over the photos to see the names. I grew to recognize them, even if I couldn’t exactly connect them to me. Here in this local history book is a Balliet: the name I carried for most of my life. This photo, a Bloss. Here’s a Schneider, a Kern. But nothing haunted me quite like the handwritten inscription that prefaced a photo album: “Presented to Kate E. Haines by her Affectionate Mother, July 18, 1866.” There were two such photo albums, small, sturdy, and so elegant they seemed out of place. Inside the albums, the trading card-sized cartes de visite showed women in dark corseted dresses and bearded men in somber coats, all sitting or standing in professional studio settings. Unlike the faces in the black-backed scrapbook, framed in glossy three-by-fives and looking out candidly from lawns and stoops, I found no familiar features in these posed men and women. They were a complete mystery. Who were they? Who was Kate? And how did my family come to possess the remnants of her life?

There were two such photo albums, small, sturdy, and so elegant they seemed out of place. Inside the albums, the trading card-sized cartes de visite showed women in dark corseted dresses and bearded men in somber coats, all sitting or standing in professional studio settings. Unlike the faces in the black-backed scrapbook, framed in glossy three-by-fives and looking out candidly from lawns and stoops, I found no familiar features in these posed men and women. They were a complete mystery. Who were they? Who was Kate? And how did my family come to possess the remnants of her life?